Steve Earle Honors Jerry Jeff Walker With New Album: ‘I Lived More Like Him Than Anyone Else’

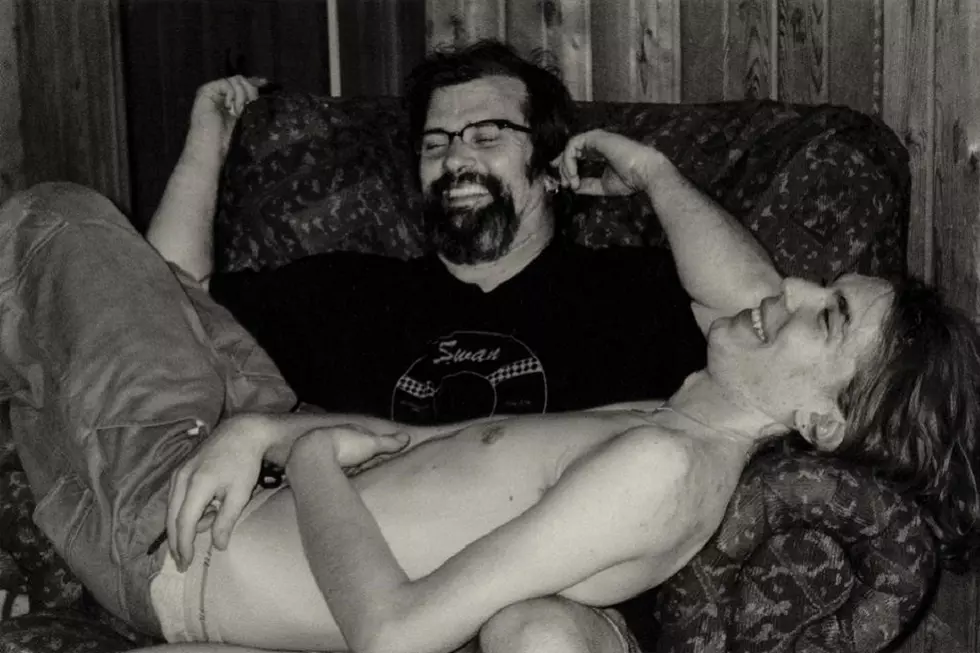

Steve Earle is sitting on a couch in a recording studio a block away from Union Square in New York City. He used to live on Bleecker Street for years, about 15 minutes away.

"I'll never forget walking around," he tells Taste of Country about living in New York in the early days of the coronavirus pandemic. "I was still here. There was one morning when it hit me, how scary this all was. There was no traffic on 6th Avenue. I had never seen anything like it."

About four months after that, Earle's life became even scarier. His son, Justin Townes Earle, died on Aug. 20, 2020, at the age of 38. Earle never spoke much about the death, but he quickly entered Electric Lady Studios near his New York apartment to put together a new album of covers of songs written by his son. J.T. came out on Jan. 4, 2021, and in the liner notes, Earle wrote, "I made this record, like every other record I've ever made...for me. It was the only way I knew to say goodbye."

J.T. wasn't the first time Earle recorded an album to say goodbye to someone, though it was undeniably his most personal and challenging. In 2009, he released Townes, a tribute to his friend and teacher, Townes Van Zandt. Ten years later, Earle released another tribute to a friend and teacher, Guy, this time in honor of Guy Clark.

Earle always knew he would have a third covers album to record, but he never thought it would be for his son. On Friday (May 27), Earle's fourth — and at least for the foreseeable future, his final — record of cover songs is out via New West Records.

Jerry Jeff Walker died two months after Justin and now, Jerry Jeff completes Earle's intended trilogy of albums honoring the men who were instrumental in his growth as a songwriter and performer.

"Townes and Guy were people I sat right across from for a long period of time," Earle explains. "I learned a lot from them. But I wanted to be Jerry Jeff Walker more than anything else in the world at one point, long before I ever even met those guys. He's the glue to all of that for me."

Texas' Connection to New York City

Jerry Jeff Walker was born in the small town of Oneonta, N.Y., just a few hours from New York City. In his early 20s, Walker was playing around the fabled folk neighborhood of Greenwich Village, though he would also often travel the country to play his brand of outlaw country and folk music. For many young, eager musicians like Earle who lived thousands of miles away from New York City, Walker was an inspiration.

"Jerry Jeff was our connection to Greenwich Village," Earle says. "Yes, there is something about the water in Texas creating songwriters, we can't deny that. But when Jerry Jeff came through Texas, he was a very big deal."

Walker's entire persona — including the fact that he hitchhiked everywhere he went — captured Earle's attention.

"Jerry Jeff didn't like to pay for transportation," he says, smiling. "Guy never hitchhiked an inch in his life. Townes did a little bit, but Guy was actually a good mechanic, so he could always keep his Volkswagen running. I wasn't a good mechanic, I didn't know you could get to Nashville without hitchhiking until I was 25."

In fact, Earle's first experience with hitchhiking was because he wanted to see Walker.

"He was the first person I ever hitchhiked to go see," he recalls. "I went up to Austin on his birthday one year and I crashed his birthday party. At the show, I overheard someone tell a girl where the party was and so I lied to this other girl and said we were invited. We got there, and not only was Jerry Jeff there, B.W. Stevenson was there, Rusty Wier was there, Milton Carroll, too, who was an absolute badass. And Bill Callery, who would later become one of my teachers."

As legend has it, that birthday party wasn't just the first time Earle was in a room with Walker, but it also was the first time he saw Van Zandt. That was a turning point in Earle's trajectory as an artist.

"Townes walks in with this white buckskin jacket with beads on the fringe and immediately he starts a dice game," Earle remembers. "He loses every dime he's got, including that jacket, in about 30 minutes. He leaves the party and I thought, 'My hero.' I stopped wanting to be Jerry Jeff Walker and started wanting to be Townes Van Zandt."

Earle describes that instance as a "big moment." Seeing Van Zandt sparked a new curiosity about the artist, and Earle started following him around Texas. About a year later, he moved to Nashville. There, he connected with Clark — eventually playing bass in his band — and through that relationship, re-connected with Walker. Though as Earle puts it, that was probably when Walker thought they first met.

"That's when we actually got to know each other," he says. Getting to know each other involved Earle working for Walker, driving him around Nashville whenever he was in town.

Laughing to himself, Earle talks about that vocational experience.

"Guy came over to my house one night, laid out a couple of lines, and said, 'Hey, I'm going to hire Charlie Bundy to play bass because you need to stay home and write songs and I need a better bass player.' Once that happened, I became Jerry Jeff's designated driver. He'd pop in from time to time and he'd call me just to drive. That's part of the reason my first marriage didn't last very long, s--t like that. I'd just say, okay, I'll be there."

Learning From Jerry Jeff Walker

Earle had a lot of teachers throughout the early part of his career. He'll name Bill Callery and John Hiatt in any conversation about teachers, but there were no more direct voices in his life than Van Zandt, Clark and Walker. Earle is quick to talk about his work ethic coming from Clark and his love of reading and learning from Van Zandt. When he thinks back on the influence Walker still has on his music, though, he brings up two specific things.

"First off, Jerry Jeff was a really, really, really good songwriter," Earle states. "But he was also a great performer. Anyone that knew him — whether they liked him or not — would say that when it came to playing, singing, performing, whatever, Jerry Jeff was better than everybody. He was funny, but he was poignant."

That connection to an audience was something Earle embraced, sometimes a little too well.

"Even when Jerry Jeff was hammered, he could do it," he says. "I lived more like him than anyone else, and I even tried going up onstage when I'd have too much to drink; I was doing that on purpose. I was emulating Jerry Jeff Walker."

Earle's new album, Jerry Jeff, finds him not merely emulating his friend and teacher, but celebrating his music with his distinct sound. Songs like "Gettin' By" and "Gypsy Songman" remain true to Walker's original recordings, but they become Earle's thanks to the work of his band, the Dukes, and his inimitable voice.

Familiar tracks like "Mr. Bojangles" or "Hill Country Rain" take on their own life, too, highlighting Earle's deep respect for Walker and his own love of being in the studio, creating music. He certainly has a knack for honoring other artists through his own music, but Earle is ready to put these efforts on the shelf for a while.

"I'm going to be working on [my stage production of the 1983 film] Tender Mercies," he explains, "and I need to make some records of my own songs. Three of the last four albums have been other people's songs. Don't worry, I'm writing songs and other s--t."

Always the student, Earle is learning a new skill, too.

"I've been co-writing with a few other folks," Earle says. "I want to learn how to write stuff that can get onto country radio these days. I don't have any idea how to write that kind of song, so I'm writing with a lot of people in Nashville right now because I want to learn how to do it."

Some fans may be surprised to hear Earle talk about wanting to get onto country radio, but he has no qualms about the music he hears on the medium.

"I'm never going to say what those guys on the radio are doing isn't country," he says. "You'll never hear that from me. They decide what's country. In 1986, when Guitar Town was out, I was playing a dance hall in Vegas and this guy kept dancing by and turning the girl around, saying, 'Play something country.'"

Earle gets a smirk on his face as he remembers this moment.

"That same week, a kid at MCA had hand-carried a box of my albums to a distributor and I beat Alabama by one f--king box to get to No. 1 on the country charts. I stopped in the middle of the song and I looked at that guy on the dance floor and said, 'Hey, you know what? I've got the No. 1 album on the country charts this week. I decide what's f--king country."

Taking all that he's learned over the years from mentors like Van Zandt, Clark and Walker, Earle still holds a similar ethic when it comes to who gets to define any genre of music.

"I believe that to this day. I don't decide what's country anymore, those kids in Nashville, those kids on the radio, they decide what's country. It's their turn. It's the way it is and I want to learn how to do it."

Country Music's 50 Best Summer Songs

More From Big Cat - Country with Attitude